Caernarfon Castle, courtesy Wikipedia

An Ordnance Survey map of Anglesey from 1946

Bryn Celli Ddu Burial Chamber, near the town of Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwll-llantysiliogogogoch

Caernarvon: 53° 08’N, 04° 16’W In the dead of night, it was hard to make out the blinking lights of navigational buoys marking the serpentine channel through the sandbar at the mouth of the Menai Straits. Off the starboard bow, there was the mainland, and the fizz of neon shop signs, halogen street lamps glowing orange, and headlights rising and dipping as cars wound along the main coastal road; there were also the bright spotlights illuminating the crumbling walls of Caernarvon Castle. Off the port bow, on the low shores of the Isle of Anglesey, were more streetlamps and a checkerboard of lighted house windows. There was nothing to do but trust the flooding tide to lift our keel over the shifting sands and carry us into the deeper water within the straits.

We avoided grounding and eventually anchored off a timber public jetty not far past the town. We had intended to sail all the way through the straits on the last few hours of the flood but that would have meant negotiating the reefs in the unlit narrows beyond the Menai Bridge in the dark, a manoeuvre that requires keeping within an oar-length of the eastern shore and regaining the buoyed main channel to Bangor just before the tide begins to ebb. However, piloting the uncertain channel through the Caernarvon bar “by touch” at night, on top of nearly losing my boat in The Tripods in daylight, had sapped whatever nerve I had left.

On the shore opposite where we lay at anchor was the Anglesey village of Tal-y-Foel. From Tal-y-Foel northwards along the same shore to Mol-y-Don, close by the improbably named village of Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwll-llantysiliogogogoch (it means “The church of St Mary in the hollow of white hazel trees near the rapid whirlpool by St Tysilio’s of the red cave), the inexorable drive westwards of the Roman invasion of the British Isles during the first century AD was almost held to a stand-off by local warriors. In AD61, Gaius Suetonius Paullinus, the brutal Roman commander who would later defeat the famed Celtic queen Boadicea, had decided to eradicate the Druids by overrunning their spiritual home, Insulis Mona – the Roman name for the Island of Anglesey (first named, again, by the Vikings) – and so undermine the resistance of the last undefeated Celtic tribes. At the same time, he could seize control of valuable grain stores to victual his army and of copper mines that would provide the raw material for new armaments.

It was never going to be an easy task. Even Rome’s ingenious miltary engineers could not bridge the fast-flowing tidal waters between the mainland and the island, and the Celts had proven themselves to be skilled if undisciplined guerilla fighters. Led by Druid priests, who invoked dark, animistic forces to come to their aid, thousands of Celtic warriors arrayed themselves along the Anglesey shore. Naked, their skin dyed blue from woad,Fro they screamed taunts at the Roman legions across the straits and beat their swords and spears against wooden shields. Their women danced between them, lighting bonfires from burning torches that they waved like battle standards.

If the intention was to strike fear into the enemy, it worked – for a short while. The Roman line was gripped by a wave of panic and, perhaps for the first time in the Empire’s history, an entire legion flinched. But Paullinus rode among them, rousing them to the fight, and as the tide slackened, his infantry crossed the water in boats – his calvary swam with their horses – under cover of a barrage of fireballs, iron ingots and rocks catapulted onto the opposition from huge “ballistae”, the Romans’ deadly prototype of field artillery. The battle-hardened centurions slaughtered the Celtic warriors, then took to massacring their families. The Druids and their acolytes were burned alive in their sacred oak groves.

Undaunted, the Anglesey Druids, the last remaining in Britain, along with the Celtic tribesmen who venerated them, rose again 17 years later. This time they faced legions led by Gnaeus Julius Agricola, who had been among Paullinus’s officers. Agricola resolved to eradicate the troublesome Druids once and for all and to subjugate this last pocket of Celtic resistance. His men, like Paullinus’s, crossed the straits by boat and staged a bloody rampage that finally wiped out the Druidic priesthood forever and broke the back of the Celtic resistance.

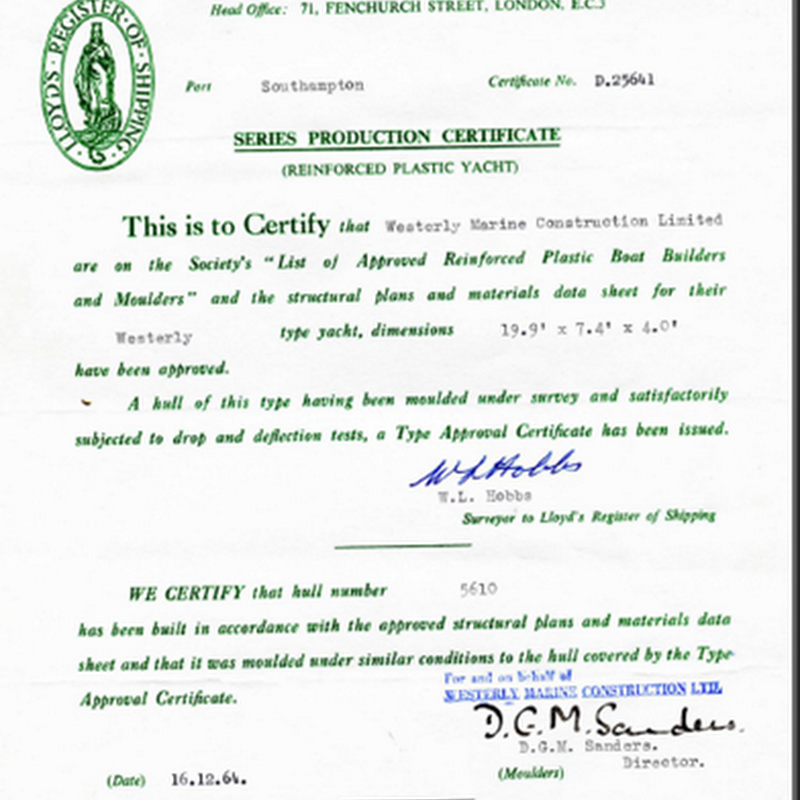

We set sail from Caernarvon early the next morning. The waters, stained a coppery brown by tannin, were mirror-like and still, and reflected the shadowy boughs of gnarled old oaks that overhung the shore. Drifting northwards on the flood tide to the Menai Bridge, I sat cross-legged on the cabin-top and tried to identify the few, stark memorials of the Druids’ last stand on a 1950s Ordnance Survey map: a rise called Bryn-y-Beddau, the “Hill of Graves” where the Celts buried their dead, “the Field of The Long Battle” and “the Field of Bitter Lamentation” outside the village of Llanidan, and Plas Goch, “the red place”. In the windless silence, it was easy to imagine it as an island of restless ghosts.

1 comment:

At once a surprise and a real honour to see my words here. Thank you. (And the photos and maps are a treat.)

Post a Comment