Phil Maynard in his stitch & glue melonseed and Mike Wick in his Bolger Gypsy heading South. The beach at Assateague, 1/4 mile walk from Green Run.

The beach at Assateague, 1/4 mile walk from Green Run.

You can see that my Gypsy has low freeboard and was prone to swamping when she was

You can see that my Gypsy has low freeboard and was prone to swamping when she was

an open boat. She was planned for rowing more than sailing.. I built the red sunbrella

deck in this picture to make her more seaworthy. It didn't help. The next winter I built

a plywood and epoxy deck that worked well.

Green Run. The campsite is up among the trees. The building is a boarded up hunting

Green Run. The campsite is up among the trees. The building is a boarded up hunting

shack, abandoned before 1965 when the Island became a national park. John's sprit-rigged melonseed with Home Depot high-tech daggerboard clamp. They are

John's sprit-rigged melonseed with Home Depot high-tech daggerboard clamp. They are

perfect for shallow water sailing.

all photos courtesy John GuiderasSee details of the Assateague trip pictured here in the article by Mike Wick below.

Ray Aldridge has a weblog named for his self built and designed beachcat Slider. It contains lots of info on the boat and beachcruising in general. He's building a database for beachcruisers worldwide, a guide to areas accesible to shallow drft small cruisers. What a great idea! But he needs your help. Read his explanation below and then enjoy the article submitted by my fellow Delaware River TSCA member Mike Wick about a trip he and two friends, John Guideras and Phil Maynard took to Assateague Island, in two Melonseeds and a Bolger Gypsy.

Base Camps

An invitation: help me compile a free base camp database, available to all small boaters on the worldwide web.

For a while now I’ve been thinking about how to make Slider’s site more useful.

I’d like to offer information of interest to small boat sailors in general, not just to those who might be interested in a boat like Slider.

One idea came to me in part because I’ve been the book reviewer for Living Aboard magazine for a number of years. Many cruising guides have passed over my desk, as a consequence, and I’ve noticed that there are very few such guides that would be particularly useful for small sailboats. There are cruising guides for deep draft cruising boats, full of dire warnings about “reported shoaling to 3 feet” and other remarks irrelevant to small boat sailors. And then there are the guides meant for kayakers, who require nothing but on-foot access to the shore, and who must be very cautious about crossing open water.

In between, there seems to be relatively less coverage of cruising from the viewpoint of small open boat sailors, despite the fact that this kind of sailing seems to be growing in popularity. And these folks have a unique perspective as to what makes for a good cruise. Even the pattern of movement is usually different with a small boat cruise. While a live-aboard cruiser tends to pass through an area from end to end, the small boat cruiser is more likely to establish a base camp and sail forth each day in a new direction, until the area is explored for a few miles all around. It struck me that small boat cruising guides might best be organized by base camps rather than cruising routes, because spending one’s nights inside a big tent on land in relative comfort, and sailing every day is one of the most popular and luxurious ways to go cruising in a small boat. Why not, I thought, try to encourage the collection of some good base camp descriptions around the country or around the world– short articles that describe one person’s idea of a perfect base camp– its amenities and costs, a description of the place and of the surrounding sights viewable from a small boat.

When I was out cruising the coast for a few days, back in September, Slider and I visited an anchorage near Big Lagoon State Park, not far from the Florida-Alabama state line. I’d visited this well-situated park before, and the other day went back for a look. I measured the ramp, took a few pictures, and generally enjoyed the park. It seemed to me that the park had everything you’d want in a base camp, so I wrote the first piece and published it on Slider’s blog:

Big Lagoon State Park

I’m hoping my fellow small boat sailors will help me put together a selection of potential basecamps from everywhere there’s good sailing for little boats. I have a list of suggestions for the kind of information I think most of us would like to see, but I’m sure I’m forgetting lots of stuff, and I hope you’ll help me out with your suggestions and criticisms.

I think each base camp article should start with a bulleted list of basic info:

- Name of base camp: If nameless, pick a name! Link to pertinent website if possible.

- Brief description: One sentence summation of the base camp’s main appeal for small boat sailors.

- Location: Country, state or province, nearby towns, mailing address, and a link to a map showing the route and a link to an online NOAA chart, if available.

- Weather and climate: Here a link to a local weather page is nice. I like Weather Underground.

- Fees: Entry fees, ramp fees, camping fees, etc.

- Ramp: Depth, capacity, condition, parking, etc.

- Amenities: a list of resources in or near the camp: shady campsites, phones, ice, grocery stores, convenience stores, service stations, ice, restaurants, motels, libraries, marine chandleries, amusement parks, other attractions within driving distance, and so on.

As many useful links as possible should appear in this first small section. I’ve undoubtedly missed some good ideas, and I’d be grateful for any suggestions for adding useful data to this list.

The rest of the piece is up to you. Whatever way you choose to get across the pleasures of visiting one of your favorite base camps is fine by me. You can develop the attractions of the site in any pattern you prefer– put it in the form of a narrative about a trip, actual or ideal, or use any other approach you think will work. I may make suggestions and edit your material a little, but I’ll ask you to approve any substantial changes before I publish the piece. I think we should keep these descriptions to under 2000 words, if possible.

Photos are very helpful, I believe, but they need not be of professional quality to greatly improve any story. Include anywhere from 3 to 8 shots, preferably sized down for the web, but I can easily do this. A shot of the ramp, a shot of an adjacent beach or dock, a couple other nice views will lend a lot of punch to the story, and give your readers a better understanding of the cruising area the base camp serves. I like pictures of living things and boats, so the best shot of all would be a beachcruiser parked on a beautiful beach, with a sailor or two busy having fun.

Base camps need not be official campgrounds of some sort. For example, I plan to write a base camp piece on a great little cruising area in my own back yard. The gateway to the base camp is a city park here in Fort Walton Beach that has nice ramps, just a couple of miles east of a string of little spoil islands in Santa Rosa Sound, created when the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway was first dredged. These islands are popular on the weekends with locals, who set up tents and spend the day swimming, sunbathing, and fishing. During the week, they are largely deserted, and can provide an almost wilderness experience just a few minutes sailing from a small but lively city, with every imaginable amenity, and across a wide shallow lagoon from the Air Force-owned portion of Santa Rosa Island, which is almost pristine.

Another possible idea, for those who like a little luxury with their cruising, is to find an inn or bed-and-breakfast in a cruising area, and make that the base camp.

Or you may know of an island with organized camping facilities that can only be reached by campers with a boat or a ferry ticket. For example, right now you can camp at Ft. Pickens on the western tip of Santa Rosa Island, if you have a boat or are willing to walk or bicycle in over a road that was destroyed by the recent hurricanes. Eventually the road will be rebuilt, but for now Ft. PIckens provides a unique kind of base camp. There are many other wonderful island base camps to be found, from Lake George in New York, to the Maine Island Trail to the Apostle Islands of Lake Superior.

I really hope folks will help me to start this moving. I believe it would be of interest to microcruisers of all sorts, particularly for those of us who sail small open boats. I can only do a limited number of these articles by myself. But I’m certain that if the small boat cruising community gets behind the idea, it will become a wonderful resource for all of us.

Contact me with your ideas!

Here's Ray's formula applied to Mike Wick's adventure sail to Assateague:

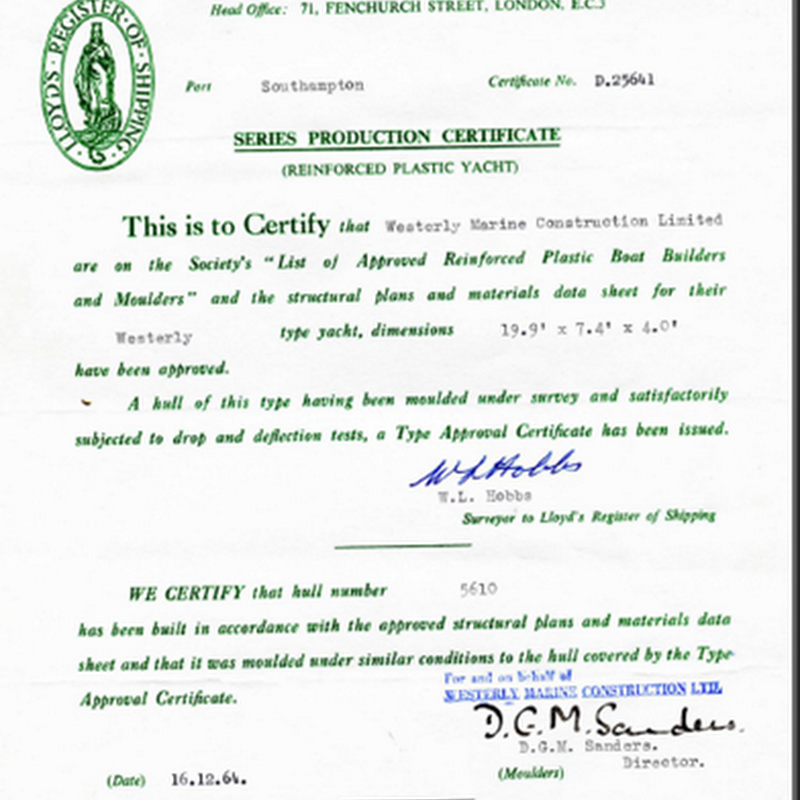

Name: Assateague Island National Seashore. Location: Ten miles South of Ocean City, Maryland. Nearest small town, Berlin, Maryland. Weather: See Ocean City, Maryland. Chart Fees: $10 entrance fee. Car Camping rates $20 per day. Remote campsites $5 per week. Significant reduction if over 62. Ramp: Shallow sandy beach at Old Ferry Landing is fine for small boats. Larger boats at either South Point launch ramp, 1 mile west or Verrazano Bridge Ramp, off Route 611 at Sinepuxent Bay. Routes: Four remote campsites on Assateague Island, 2,5,10,12 miles South of National campground. Two day, 30 mile passage South to Chincoteague Island. Eight mile passage north to Isle of Wight Bay inside Ocean City. In brief: The Eastern Shore is on the primary flyover for birds migrating up the East Coast. There are extensive shallow water passages on the bayside of Assateague Island with clamming and mussel harvesting opportunities.Can be hot and buggy in the summer. Best seasons are late in the fall and early in the spring. Mosquitoes are worst after multi-day rains.

Many thanks to Mike Wick, who contributed this information, and the story that follows. Looking at the chart, this appears to be a paradise for small shallow draft boats.

There were three of us in three boats, three cars, three trailers. We had decided that we would sail the length of Assateague Island, campcruising along the way.The latest weather report showed that the wind would be mostly out of the North for the next few days, so we decided that we would sail South from Assateague Federal Seashore toward Chincoteague Island. I arrived at Old Ferry Landing and launched my Bolger Gypsy, dropped off my trailer near the Ranger Station and drove South to Chincoteague. I found a quiet parking place and cell phoned Phil, who drove straight to Chincoteague and picked me up. He and I drove north in his pickup truck, launched his melonseed and launched John’s melonseed. We left their cars and trailers at the Ranger Station.Thus, we had two cars at the North end of the Passage and one at the south end.

It was about 11 A.M. when we set sail in convoy from Old Ferry Landing in a light northeasterly breeze. We passed the Tingles and the Pine Tree campsites in smooth water with a lee from Assateague Island keeping down the waves. Seldom is the water much more than knee deep if you are outside the Intracoastal Waterway, so there is no anxiety about swamping or capsizing, you can just walk ashore. We rounded the point of the island in the channel between Green Run and the Pirate Islands.At this point, the wind had picked up enough to warrant a reef, but there was less than a mile of windward work to our destination, so we just luffed along toward our destination. By six we had reached our remote campsite at Green Run, ten miles south of the large campground at the Federal Seashore.

Green Run is a nice shady campground with picnic tables, fireplaces for each group, and a portapotty. but there is no potable water, so we had each brought three gallons with us for drinking and cooking. A quick meal and bed in our tents; we were too tired for a campfire.It is a short walk to the ocean with a beautiful beach, and we had a quick swim before bed.

The next day was sunny and light air, just enough wind to ghost along. That section of the passage is an intricate maze of quite shallow channels inside swampy islands. We beat up a river to the most distant campsite on the Island, Pope Bay wehre wwe stopped for lunch and walked over to the ocean beach. Here we realized that, if we kept sailing, we could finish our passage that night, so we rushed out to Chincoteague Bay and sailed across the Maryland/Virginia border. It was a lovely plain sail beat in a brisk Southeast breeze of maybe 12 miles an hour wind. We passed to the East of Wildcat Marsh, on the northern tip of Chincoteague, tacking in close company to the haulout at Quip Hole Road, just inside Morris Island.

Then came the strenuous part. I walked into Chincoteague to retrieve my car, then I drove the others to Assateague for their cars. It was dark by the time we got our cars and trailers back to the ramp, but we were practiced at packing boats on trailers, so it went smoothly even in the dark. What could have been a problem, we decide to drive straight home. We probably should have stopped at a nearby motel, but we made it safe home about eleven, even though we were tired and bug bit. We had made a nice thirty mile, two day passage in company and had seen parts of the refuge that were new territory for us.

Posted in: Base Camps for Beachcruisers, Cruising, Sailing. Tagged: Base Camps · beachcruising · Cruising · Maryland · national seashore · Virginia