courtesy Umilta

courtesy Wikipedia

courtesy Stephan Vaughan

.jpg)

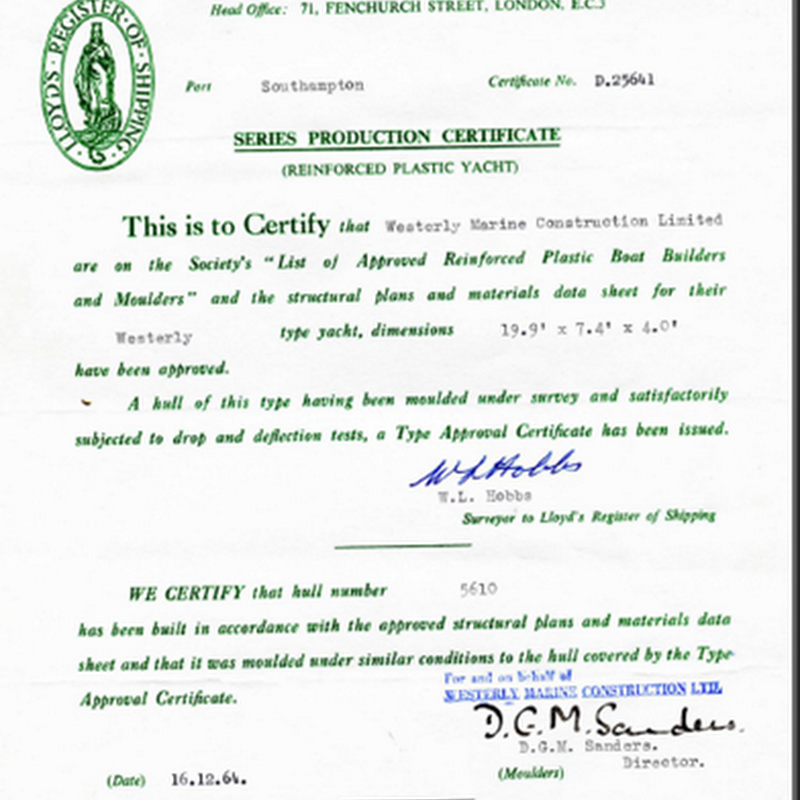

Supeachilles, Creed's vessel for this voyage. Courtesy Creed O'Hanlon

NORTHING part 2

by Creed O’Hanlon

It is not down in any map; true places never are.

Herman Melville, Moby-Dick

Lymington Quay: 50° 45.2’N, 1° 31.7’W Every summer, in every boatyard along the south coast of England, there was at least one crew preparing a yacht for a trans-Atlantic crossing. Most wouldn’t be ready in time – some never would be – but those who managed to work through their endless lists of yardwork, everything from replacing running rigging and reinforcing sails to checking rudder posts, pintles and gudgeons and antifouling the hulls, might finally cast off in early autumn and make for the warm waters below the 35th parallel.

The usual track was south-west, passing well offshore of the fearsome reefs and tidal races around Ile D’Ouessant, at the south-western corner of the English Channel, to cross the unpredictable maw of the Bay of Biscay to Cape Finisterre (in English, “the end of the world”). From there, they would make either for Gibraltar, at the entrance to the Mediterranean, or, more likely, the volcanic Canary Islands, off the coast of southern Morocco, where, like Christopher Columbus’s exploratory fleet 500 years before them, they would rest, make repairs and reprovision while they waited for the North Atlantic hurricane season to abate. Sometime in November, they would set off south-west again towards the Cap Verde Islands, standing well off the African coast. After drifting through the humid calms and sudden rain squalls of the Horse Latitudes (a region between the 35th and 30th parallels dominated by a sub-tropical high and so named because, according to tradition, ships often lay becalmed for weeks there and their crews, fearful of running out of water and victuals and, worse, becoming afflicted by scurvy, threw cargoes of hungry horses and cattle overboard) they would pick up the north-easterly trade winds and, at last, alter course westwards, freeing their sails. A relentless wind off the starboard quarter and an easy following sea would carry them on an even keel all the way across the Atlantic to whatever islands in the Caribbean they might be bound.

I had lived and worked on the sea for half a decade. I had crossed the Atlantic twice, both times from west to east on a northerly route that took advantage of the Gulf Stream and the prevailing westerlies but was always hard, cold sailing, and never without a gale springing up within one of the low-pressure systems that followed one after the other with tedious frequency across the Atlantic’s higher latitiudes. Once, during a leaden English winter, while I was helping a friend rebuild a 50-year-old Hillyard cutter in a cluttered boatyard on the Lymington River, relaying and caulking its timber decks in the few hours of rain-less daylight, I thought about sailing with him on the long, warm-water voyage to the southern Caribbean that he had planned for the following autumn.

And yet I knew somehow that I wouldn’t. There were no clear skies, fair winds or landfalls on palm-fringed cays in the voyages I made in my imagination; instead, the coasts were tree-less, steep and rock-strewn, beset by fast-running tidal streams and angry seas the same colour as the slate-grey skies. I daydreamed of high latitudes, of retracing routes once sailed by Norse longships, Phoenician and Celtic traders (the Veneti, a Celtic maritime tribe, ferried tin mined in Cornwall to the Gallic mainland), imperial Roman battle fleets and and even the leather-hulled curraghs of fifth-century Christian monks. A trade-wind passage was dull compared with the demands of navigating the treacherous jigsaw of reefs, skerries and precipitous islands and the constantly changing weather conditions to the west and north of Wales, Ireland and Scotland, where tidal races tripped over jagged shoals faster than a small yacht could sail.

But there was more. In the north, every headland, channel, loch and narrows was haunted by legends – and a few, by dark superstition.

“Maybe one day you’ll fetch up in Ultima Thule,” my father would tell me. It was he who first told me about Pytheas of Massalia, a Greek who, in 330BC, set out from what is today the Mediterranean coast of France on one of the first recorded voyages to the far north Atlantic. In his book, About the Ocean, which has been lost for more than a millennium but is quoted in other ancient texts, Pytheas described landfalls on the British Isles and possibly Ireland, after which he voyaged northwards for six days to Ultima Thule, which he described as being at the edge of the known world – just a day’s sail from what he called the Cronian (or Frozen) Sea – where the nights were very short and in the gelid mists, the earth, sea and air became indistinguishable from each other. The exact position of Thule was lost with Pytheas’s work and although, over the centuries, famed explorers such as Columbus, Sir Richard Francis Burton and Fridtjof Nansen claimed to have found it on coasts as distant as north-west Norway, Iceland and the Shetland Isles, it’s unlikely any of them did. As the contemporary author and Thule researcher, Joanna Kavenna, has written: “Ultima Thule was a land beyond the reach of humans, a place entwined with the outlandish – unipeds, the seven sleepers, a great whirlpool at the Pole, the ocean’s navel.”

Still, the iron-bound coasts and windswept seas that had to be negotiated even to have a chance of reaching it were the birthplace of many of our best-remembered legends, first told in millennia-old languages that still endure.

2.JPG)

No comments:

Post a Comment